Participatory techniques and conservation programs

Samoa Conservation Area | Pohnpei, FSM conservation area | Forest Conservation in Vanuatu |

|The Tongan Environmental Awareness Week|

Participatory techniques have proved especially helpful for environmental planning in the Pacific islands. The SWOT analysis and analysis of conflicts in environmental issues stress the need for community participation and understanding in environmental planning. The following are some examples from the Pacific islands where involving the community made a significant difference in results.

The Samoan Uafato Conservation Area

The O le Siosiomaga Society is a local Western Samoa environmental NGO. They have instigated a number of community oriented projects in Western Samoa. Their newest and most interesting project is the "Uafato Conservation Area." The Society has a proposal before the Global Environment Facility’s South Pacific Biodiversity Conservation Programme co-ordinated by SPREP.

Uafato is located on the Northeast coast of Upolu. The conservation area includes a virgin rainforest, the coastline, the coral reef and adjacent marine areas as well as the village itself.

The project has, from the start, worked with the commitment and management skills of the traditional landowners in partnership with the management and technical support of the Siosiomaga Society and the Department of Lands, Surveys and Environment. Local participatory planning and management is provided by the Uafato fono (village council). The fono appointed a conservation area coordinating committee to oversee the management of the site. The committee consists of the village pastor and local matai and representatives from village groups such as the faletua ma tausi (wives of matai), taulelea (untitled men), wives of taulelea and aualuma (unmarried women).

The fono is in the process of establishing the conservation area covering the village rainforests and adjacent marine areas. The management team, made up of villagers, the O le Siosiomaga Society, and government agencies will collect resource data and coordinate management policy to assure sustainability of the conservation area. This is still in the planning stage.

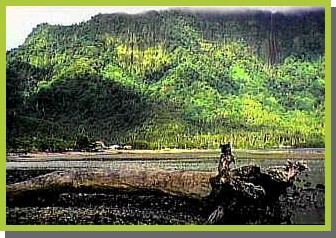

The village is at the head of a deep bay and is surrounded by steep mountains covered with primary rainforest. The rainforest was rated as a grade 1 priority site for conservation (Park et al 1992). It is one of the few places in Samoa where there is an intact band of rainforest from the sea to the interior and is thought to be one of the most viable areas in Samoa for conservation that will sustain the natural ecosystem in perpetuity along with the traditional forms of resource use.

The fono has already placed restrictions on access to the forest and sea and have banned the use of chemical pesticides, dynamite, and fish poisons. While the ban is effective in the forest and coastal area, fishers with boats from a neigh boring village have violated the ban on fishing in the village conservation area and the fono has been unable to do anything about it.

The project is committed to assessing and monitoring biodiversity data and levels of village use of resources. The surveys and monitoring will be performed with the assistance of the DEC and consultants. The initial surveys will establish long term monitoring activities for key species and habitats.

Uafato:

Uafato was one of the original settlements, dating back 2,500 to 3,000 years ago (Green and Davidson 1981). The rugged topography has a strong scenic attraction but 90% of the village customary land is unsuitable for agriculture due to the steep slopes and poor soil.

The population of Uafato was 234 in 1991. This is divided into 17 extended families (aiga), some with 2 or 3 households. The population peaked at 287 in 1971 and then declined throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s due to out-migration. A household survey revealed each nuclear family had an average of 5 children living overseas. The village is typical of most Samoan villages. It is located on the coast with a central village green (malae) in front of the church. There is no store. Small plantations extend up the slope behind the village.

The village economy is subsistence based. Only 8 of 102 economically active people have a wage job and these work in Apia returning during weekends. The only economic activity is handcraft production including wooden carvings and woven items. 87% of respondents in a village survey reported income from handicrafts. Remittanes from family members overseas were another important source of money.

Farming is the most time consuming economic activity. 75% of the agricultural land is under coconut. Breadfruit, bananas and root crops are grown in small plots under shifting cultivation, often on steep land. Fallow periods are short (one to two years) due to the limited available land and rich soil.

The People:

Uafato is a traditional village governed by the matai system. The basic social unit is the extended family (aiga) headed by a matai or chief appointed by consensus of the family. The matai directs the use of family land and other assets, including labour.

The village matai make up the village council or fono. Under the Village Fono Act 1990, the fono has legal, judicial and executive powers. The fono has substantial influence on village life, regulating activities, mediating disputes, and passes rules, restrictions and enforcement of resource use.

The second major social institution is the church. About 80% attends the local Congregational Christian Church and a small number attends the Mormon church in a nearby village. The church is the focus of social and economic activities and the village pastor has considerable influence on village life. In Uafato, the village pastor is the focal point for the Conservation Area project.

Other village groups include the Women’s Committee and the Untitled Men’s group, a wood carver association and a Christian Youth Group.

The decision making process is done by the men but the women play a strong role in village life. The Women’s Committee represents women’s rights to the village council and organizes community based activities including village hygiene, sanitation and beautification. Women participate in fishing activities by gleaning the reef at low tide, turning over rocks to find shells and other eatable invertebrates.

Fisheries:

The Uafato bay is deep, with a narrow fringing reef extending less than 300 metros off the coast. The corals of the reef top were reportedly destroyed by Cyclone Ofa in 1990 and showed no signs of recovery in February 1997. The reef top is coral and basalt rubble and the beach in front of the village has experienced some coastal erosion since the Cyclone. Larger stones and coral fragments have a moderately well developed invertebrate fauna under them.

Corals on the upper reef slope were also destroyed but a 1995 community survey found coral cover returning (no survey was done immediately after the Cyclone to document destruction). The community survey found extensive development of tabulate Acropora hyacinthus on the southern reef slope and a wide variety of massive, branching and other corals on the western side of the bay (Siosiomaga 1996). The bay is an important big-eyed scad fishery (Stelar crumenopthalmus) and local fishermen say it is relatively unexploited.

There are two motorized, aluminum catamarans (alia), one supplied by the O le Siosiomaga Society and the other privately owned by the only full time commercial fisherman in the village.

Eighty Seven percent of respondents in a household survey said they regularly fished or collected marine creatures for food. Most of the fish is eaten by the family. 65% of households have a canoe (paopao). Most fishermen fish 3 to 4 times a week. 40% fish inside the reef, 30% on the reef, and 30% outside the reef. They use hand lines, nets and spears. Most fishing is done at night.

Fishermen noted that some species are rare, including giant clams, lobster, and turtles. 57% felt these species should be protected in some way. Fish consumption is estimated to be about 35 kg/person/year.

Institutional relationships:

Uafato has a continuing relationship with the O le Siosiomaga Society in the development of a conservation area. The project officer lives in the village for a portion of each week and holds regular workshops on conservation topics. It is this intimate association that influenced the fono to agree on an extensive resource management scheme.

The Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

The nearest DAFF district office is at Taelefaga in Fagaloa. DAFF has agreed to assist the conservation effort by providing technical assistance and advice. The AusAid funded fisheries extension project will work with Uafato fishermen in management of the fisheries resources.

The Watershed Management Section of the Forestry Division will assist in propagation of indigenous trees for planting in watershed areas and will help develop a nursery and train villagers to run it.

The Department of Lands, Surveys and Environment (DLSE)

The Division of Environment and Conservation (DEC) manages national parks and reserves. It has conducted ecological surveys and provided environmental education activities for Uafato. It will continue to assist the village in setting up the conservation area, assessing and monitoring biodiversity, and providing amenities for tourists.

The Western Samoa Visitors Bureau (WSVB)

The WSVB promotes Western Samoa as a tourist destination and is helping develop ecotourism in Uafato and other places of special natural interest. There is already an Uafato rainforest tour and the WSVB will promote the area as a unique historical, cultural and environmental site.

Project training requirements:

Village personnel will require training in participatory project planning and management, biodiversity surveys, sustainable resource management and participatory monitoring and evaluation of ecosystems. In addition, the community requires educational materials on biodiversity conservation and the need for sustainable resource management.

Siosiomaga Society (1996) Uafato Conservation Area Project Western Samoa. Project preparation document to the South Pacific Biodiversity Conservation Programme. 1996.

Participatory resource management for conservation in Pohnpei, FSM.

In the early 1980's deforestation of the steep slopes of the interior of Pohnpei and resultant pollution of the watershed resulted in the creation of a 5100 ha forest reserve. At the same time a 5,525 ha mangrove forest reserve was designated to protect the coastal zone. The protected areas were designed to safeguard water supplies, cultural and archaeological sites and the diverse flora and fauna. The areas were also to be used for ecotourism and recreation.

When survey teams tried to mark out the boundaries of the reserves, they were threatened by angry villagers armed with sticks and bush knives. The government quickly backed down and deforestation, largely to plant kava (a valuable social drug crop), continued.

In 1990, the government formed a Watershed Steering Committee to promote watershed conservation and develop a long-term strategy. The Committee conducted an island-wide education and consultation programme. Their approach revealed a strong community desire to participate actively in planning for their own future. The Pohnpei Division of Forestry, with the assistance of the Nature Conservancy, formed a Watershed Management and Environment Project that integrated modern resource management methods with traditional decision making structures and local sociocultural conditions. They created a GIS to show the loss of forest over time and identify areas of land-use suitability for the whole island. Using a Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) process, they identified community values and areas of sensitivity such as tabu sites.

Community action plans were drawn up with the help of the high chiefs at the municipal level and village chiefs at the local level. The process of consultation and participation in the long term plans for the watershed areas lead to a request by villagers to extend resource management to the entire island, from the mountain tops to the edge of the lagoon. "The ultimate success is likely to depend on the devolution of authority from the State government to legally empower local decision makers." SPREP Environmental Newsletter April-September 1996.

Forest Conservation in Vanuatu

Logging is a concern in Vanuatu as it is in PNG and the Solomon Islands. The Vanuatu Government has a GIS system developed by a Forest Resources Inventory of the country’s land resources (Bellamy 1993). The Forest Resource team suggested key conservation areas to protect ecologically important biosystems from logging. Initial attempts by the government to lease forest land for conservation areas were time-consuming, expensive, and eventually unsuccessful (Tacconi & Bennett 1994).

The Vanuatu Government, frustrated by the resistance of the land owners to conservation measures, began a participatory programme to determine if the landowners themselves might be interested in setting up conservation areas to protect their own resources - as opposed to the Government leasing the areas from them. The project used the Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) system to investigate the needs and priorities of the people. Important elements of the PRA method were:

- Introductory meeting: During an initial meeting with the chief(s) the workers stressed that the objective was to help landowners assess their own conservation needs and wants, if they were interested in doing so. They made it clear that the National Government and the local council approved of the idea of conservation areas but that nobody was able to - or interested in - forcing these ideas on the landowners.

- Participatory Assessment

Meeting with landowners: Three issues were discussed

prior to the assessment of local conservation needs:

- Positive and negative aspects of logging operations in relation to ecological and socioeconomic impacts.

- The meaning of resource conservation.

- The concept of a protected area.

The assessment of conservation needs and wants and the allocation of resources was carried out through open-ended discussions. The major issues addressed were introduced with questions:

- Should logging activities be allowed in the area, or part of the area? If so, in which areas?

- Should agricultural activities be carried out in any part of the area being considered? Is so, in which areas?

- Should water sources be protected? How should they be protected?

- Should specific forest resources and/or marine resources be collected for commercial and/or subsistence purposes? Should the use of some of these resources be banned?

- Should some of the resources, considered above, be left for the use of future generations?

- Should a protected area be established? What area should it include? What is the term of the protected area?

- Are the resources allocated to consumption sufficient for the population (current and future) living near to or in the area?

Follow-up meetings Additional meetings were held as required to discuss the issues that developed during the first general meeting.

The system was successful at defining and proclaiming conservation areas with the landowners themselves acting as guardians and monitors of the areas.

The Vanuatu Sustainable Forest Utilization Project

In 1995, AusAid expanded the Community Development component of its Vanuatu Sustainable Forest Utilization Project. The objective was to develop community forest-use awareness in targeted rural communities in Vanuatu. The project used PRA/extension workshops. An evaluation report (Hassell & Associates 1996) found:

"the PRA process encourages villagers to evaluate their land resources in terms of their normal activities and empowers villagers by allowing them to own knowledge generated by themselves. It also provides a new and relatively structured way for forestry staff to work with communities and encourages them to respect the communities with whom they work. It has the potential to encourage women and young people to overcome cultural barriers to public expression of their views and needs, and to make men aware of the needs of the less powerful groups in the community. Finally it can encourage villagers to take action to address problems they have identified."

The review found a wide range of problems in the way the PRA was actually done. The primary problems were:

- poor choice of target villages (usually selected because they were easy to get to);

- poor contact prior to the meeting;

- a lack of clarity of what the whole process was about;

- a superficial rushed approach with minimal follow-up.

- Extension materials tended to become the property of individuals and were often unavailable to the public.

At the end of the workshops, no efforts were made to develop specific actions which the community could undertake nor to identify key individuals and organizations who could participate with follow-up actions.

Recommendations were made to improve the workshop process and the range of extension materials for forestry officers. This resulted in two initiatives, the preparation of a field manual Participatory Rural Appraisal for Community Forest-Use Awareness (Neave1995) along with posters explaining land use options, the Code of Logging Practice and the Logging Agreement, theatre presentations, videos, and radio programs.

Lawson (1997) identifies the major problem as one of conducting PRA as if it was a single project. A great deal of time and money is spent to set up the initiative and do a Participatory Rural Appraisal and then that's it. This is a far cry from establishing a long-term partnership between the community and a government agency and generally results in an initial village excitement followed by a total vacuum of activity.

The Department of Forests dropped the PRA project approach in favour of improving the relationships between Forestry Officers, both in Extension and Utilization, with the Vanuatu communities. The goal was to develop a very close relationship with the community in which the extension agents work to pass on the real decision making power to the community itself (where it actually resides anyway). The problem was that the Forestry Officers were unskilled in dealing with either their own behaviour in groups or the behaviour of others.

The Department of Forests developed a training course to:

- Improve extension and organisational skills.

- Practice on-job assistance and guidance to individual officers in the field.

- Review the progress of the first two stages.

- Reconvene the participants to discuss the findings, integrate changes and upgrade skills.

The objectives of the first, week long intensive training course - held in isolation in a small resort on the island of Santo - were to:

- Encourage Forestry Officers to move from a reactive to a proactive work style.

- Enable Forestry Officers to examine and understand their own motivations.

- Help Forestry Officers to assess and understand their leadership styles.

- Provide Forestry Officers with a useful method for assessing their thinking and problem-solving styles and the way they operate in a group.

- Expose the Officers to real-life problem situations and simulations which require effective thinking and problem solving methods for resolution.

- Provide the Forestry Officers with tools which will help them evaluate their own strengths and weaknesses on the job.

- Provide the opportunity for the Forestry Officers to reflect on the application of the material to their actual work situations.

It was one of the better training courses and one that should be a model for future extension activities in the Pacific islands. Participants have continued to use their training as the participatory process in Vanuatu expanded into a government wide Land Planning Project.

The Tongan Environmental Awareness Week

Starting in 1984, as the result of a training course in environmental radio broadcasting (Chesher 1984), the Government of Tonga began an Environmental Awareness Week. It has continued every year since and is one example in the Pacific islands where one can point to positive changes in the environment resulting from the change in behaviour of the people.

The project involves a week long celebration of the environment, with schools, businesses and government offices participating in a variety of activities. Although individual projects and themes vary from year to year, the week usually includes:

- On Sunday the churches discuss the environment and people's obligation to protect it.

- On Monday everyone cleans up the island; a massive campaign of sweeping, litter collecting, and trimming of hedges and lawns. Prizes are awarded for the tidiest village.

- On Tuesday, the Agriculture Department provides seedling trees for free and thousands of people plant thousands of trees on public and private property.

- On Wednesday there is a contest for the best songs, dances and artwork posters for the environment.

- On Thursday there is a radio talk-back show where people call in to ask a panel of key government officials for information on environmental topics.

- Radio shows each day of the week on different environmental issues.

Trees planted in the first environmental awareness week are now 13 years old. Not all of them have survived, but each year thousands more are planted; fruit trees, nut trees, decorative trees, medicinal trees. It is one of the few examples where one can return more than a decade after an environmental project started in the Pacific islands and find a measurable improvement in the flora.

Environmental awareness weeks are also conducted in Samoa and American Samoa and other Pacific island countries, but Tonga has consistently had the largest and best organized programs. The fact that the week happens to be in June, at the same time as the King's birthday, helps the festive spirit and the government commitment. It's success also centres on the realization by the Church, NGOs, schools, government departments, and businesses that the Environmental Awareness Week is a time for co-operation for the benefit of the whole community. Radio has been a big help and, in more recent years, television. People get involved.