The Tongan Community Giant Clam Sanctuaries

The Essence of Environmental Improvement |Let everyone make their own mistakes|Public Awareness and Action brings success | The Strategy for the Community Based Phase | Key people make all the difference | Social Obligations | The real success | 10 years later| Brood Stock Reserves in other countries | Cultural precedents | Video as an important aid|Do the Sanctuaries actually work? | Outline of the project steps | References

THE ESSENCE OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPROVEMENT

The Giant Clam project of Tonga began when I realized, in 1985, that most environmental programs in the Pacific were not working and probably would never work. I was a consultant for the South Pacific Regional Environment Program (SPREP), on my way to Saipan to conduct a course in environmental project planning. In preparing for the course I came up with a general definition for the end goal of environmental planning. It was this:

A successful environmental improvement program changes the way people behave so there is a measurable improvement in the flora, fauna, or condition of a resource.

Sound right? When I tried to think of some good examples for my course participants I realized there are few places in the Pacific islands can you go back to after 5 or 10 years, point your finger, and say, "There, right there, is a measurable improvement in the flora, fauna, or condition of the resources because of a well run environmental project." Environmental projects were simply not geared to accomplish that.

I decided I would give it a try. I knew I was setting out to change a cultural behavior pattern, so I picked the northern island group in Tonga - Vava'u. There are only 19,000 people there, all Polynesians, all closely related, with cultural ties going back more than 2,000 years. This eliminated the problem found in urban areas where multi-cultural mixes and transient people can destroy a project in a few minutes.

I picked a very simple social/biological problem. The giant clam Tridacna derasa was on the verge of local extinction. There was no commercial or political or social reason against preventing the extinction, so the project would not be controversial (or so I imagined at first). There was an excellent reason to preserve the species, the people simply loved to eat them.

Biologically, the problem and its solution was easy enough to understand. As long ago as 1979, New Zealand marine biologist J. L. McKoy warned the government of Tonga one species of giant clam, Hippopus hippopus was probably extinct and another, Tridacna derasa, was on the brink of extinction. Giant clams start out life as males and, after 5 or 6 years, become hermaphroditic although evidence showed they did not fertilize themselves. The clams become big egg producers after they are perhaps 10 to 15 years old. Put simply, there is nowhere in the Vava'u island group where someone does not look at the bottom in shallow water within a six year period. And every diver who sees one of these tasty critters picks it up. In the 1960's aid projects intent on economic development introduced the equations that Fish Resources = Cash. This formula was applied to giant calms. After a few months of dedicated claming using modern diving gear, the population of large adults vanished.

The biological solution was simple; gather remaining big adults, put them into a shallow water sanctuary where they can breed successfully, and leave them alone. I was not, after all, going to ask the Tongans to DO anything, I was going to try to get them to NOT do something.

The first lesson I learned was that if I wanted to try something like this I would have to do it without any official support. SPREP, which even then was the established wholesale broker for conservation aid funds to the region, backed off from the idea instantly. The problem was twofold:

- What would happen if the people stole the clams?

- What would happen if the larvae of the clams simply floated off to sea and there was no local recruitment?

The project might fail.

Aid projects are not supposed to fail.

This is why aid projects are almost always seminars, workshops, consultant reports, and surveys; they can't fail. Aid project goals have to be clearly achievable from the start. This one was risky, too risky. I saw this, and still do, as a major failing of the regional and international aid programs. Their goals are not linked to measurements of any improvement in the environment. This failing is not limited to natural resources, but extends to the Regional Youth Programs, Women's Programs, and other social development issues. Aid projects almost always base their "success" on the completion of a workshop or a report - not on measurable progress.

My attempts to get funding stressed that Giant clam sanctuaries could help solve the problem of how Pacific Island Nations can regulate the giant clam - and perhaps other - coastal fisheries. It is almost impossible to enforce size limits or other fishery regulations in the small, remote islands of the Pacific. By protecting brood stocks in community based sanctuaries and letting people catch and eat the young that settle down outside the sanctuary, the problem of maintaining the stock is much easier and very inexpensive. Nobody has to feed or care for the big clams; just place them in a sanctuary and convince everyone to leave them alone. The only maintenance needed is the replacement, once a year, of any big clams which may have died. Since the giant clams may live for more than one hundred years, new ones don't have to be added very often. Providing, of course, nobody steals them from the Sanctuaries.

But I couldn't convince anyone the ordinary people of the islands would be able to overcome the temptation to steal the clams. I suggested that if we could not get people to protect a creature they all liked from extinction we might as well find other ways to spend our time. This was an easy problem, surely it could be accomplished. Nobody but me thought it could, at least not with enough conviction to support the project.

Tonga had just set up a very successful Environmental Awareness Week. One of the questions called in over the radio on a radio talk back show was, "We are planting trees to help the land, what could we do to help the sea?" When this question was passed along to me by the Secretary of the Tongan Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources, Sione Tongilava, I quickly suggested that the people could participate in planting Giant Clams. This met with the same cool reception and the belief that the project would turn into a giant clam bake. But the idea was planted and they didn't say no. Over the next two years I kept sliding the idea back into the works at every opportunity. Over coffee breaks at a regional workshop, for example, I told the representatives of all the other countries about the Tongan plan to start giant clam sanctuaries. The glowing account of their plans was duly admired by all the participants and eventually, the suggestion moved into action.

Let everyone make their own mistakes

During Environment Awareness Week of June 1986, the Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources paid fishermen to collect 100 large adult Tridacna derasa (known in Tonga as Tokanoa molemole) and arrange them in circles on a reef in Nuku'alofa Harbor. This brood stock sanctuary would, it was hoped, improve spawning success and rebuild the numbers of this endangered species on Tongatapu's coral reefs.

Fisheries was skeptical of the whole project. They felt, quite simply, that people would steal the clams. In fact, everyone thought this would happen, from 10 year old boys to the King. Someone, I was patiently told by nearly everyone, would raid the brood stock area and kill the giant clams, thus making the situation worse, not better. But, in the absence of any laws or regulations against fishing the clams, and the absence of any conservation force necessary to supervise such laws, fishermen would eventually take the large clams from the reefs anyway. Surveys showed there were no juvenile Tridacna derasa on the reefs within easy reach of fishermen, and this proved the scattered adults were not successfully spawning anyway. Why not put them together and at least try to make a sanctuary work?

The viewpoint of the critics was, in itself, revealing. In 1986 neither Government officials nor the general public believed a marine sanctuary for giant clams would survive without a 24-hour guard. This was a self-perpetuating, negative belief system. If everyone agreed the clams would be stolen, many individuals thought they might as well take some before the clams were all gone.

The negative community self-image prevented any self-help action towards the improvement of local marine environments. Resources were expected to continue to decline, and future generations of Tongans would inherit even greater poverty and hunger. The goal of the giant clam sanctuary project was to change this attitude: to develop a way for rural island communities to improve the marine environment.

So the Ministry of Lands and Survey and Natural Resources guarded the sanctuary in Nuku'alofa Harbor. A boat with two men moored over the sanctuary every night for two years. The Ministry realized they would not be able to defend the giant clams against thieves indefinitely. In addition, since no base line studies had been made, nobody could prove if the brood stocks really enhanced the natural stocks. Critics insisted the larvae would simply float off and be lost at sea.

Public Awareness and Action brings success

My original plan was quite different from what the Government was doing. Their lack of faith in the village people and their ardent desire not to fail (and be laughed at) argued against the project being done in Vava'u where they could not afford to keep a constant eye on the clams. I suggested that if I did the project, and not the government, it would be my disaster if people took the clams from any village based sanctuary in Vava'u.

I firmly believed (or hoped anyway) that if people fully understood the reason for giant clam sanctuaries, they would voluntarily - as a community - set up, protect and maintain the brood stock of clams. In essence, the people of the community had to decide the giant clam sanctuaries were necessary. They had to decide taking giant clams from the sanctuary was an immoral act, to be punished by peer-group displeasure (Hudson 1984b). But how does one go about helping a community make that decision?

Communities, like individual people, have habits and habits are difficult to change. In Tonga, people habitually use the marine resources as common property. According to common law, no person can prevent any other person from taking whatever they like from the sea - especially when it comes to feeding the family. The result of this morality is, "If I don't take that small clam, the next person will" (Halapua, 1982). There were few legal restrictions on what can or can not be taken. With the exception of a handful of species listed in the Birds and Fish Preservation Act, there were no seasons, no size limits, and no enforcement. (Today, the new Fisheries Act imposes seasons and size limits, but nobody enforces the law).

In prior generations, Tongan people took what they needed from the reefs to provide food for their families. When they had caught enough to eat, they stopped fishing. The promotion of commercial fisheries in the last few decades changed that. Fishermen obtained expensive boats and outboard motors with development bank loans. This created a new kind of fisherman - one who would fish for money and not stop fishing until the desire for cash was satisfied. As everyone knows, the desire for cash is never satisfied. Commercialism, modern diving equipment, outboard motors and seaworthy fishing boats were common in Tonga by 1987, so the lack of a community conservation ethic was a problem of this generation and the future. Without face-mask and flippers, without a modern boat, large adult giant clams in 5 to 30 meters depth and open water conditions were reasonably safe. But they were rapidly vanishing as technology outstripped morality with devastating results. The Tongan shallow water marine resources were overfished and the coral reefs badly damaged (IDEC 1990).

Changing public beliefs is hard, changing public behavior is much more difficult, but it is the most necessary task of environmental improvement. Whenever a community acts to preserve a resource, individuals must sacrifice their own personal interest. In the case of the giant clams, individuals had to overcome their personal desire to kill the clams in the sanctuary; even if they were very hungry or wanted to sell the meat for money they truly needed. During the progress of the Giant Clam Sanctuary program I often thought how hard it would be to have one's children crying from hunger at night with 100 large and delicious giant clams right there in front of the village. What kind of incentive would be needed to overcome a father's need to feed the family? The Tongan legal system would never fine or jail someone for obtaining food from the sea for their family, sanctuary or not.

But while such a situation could happen, in actuality, hunger is not a big problem in rural Tonga. Overeating and junk food is more of a health problem than starvation.

If the community feels it is more important for an individual to have easy access to food than to protect the clams for future generations, the clams won't survive long. If, however, the people feel the survival of the clams in the sanctuary are vital to the maintenance of their social obligations, nobody will harm them.

If the community fails to achieve some kind of serious conservation ethic, the resources will continue to decline and eventually result in increased poverty, hunger, and dependency.

The Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources realized the need to develop the public's awareness about the usefulness of marine sanctuaries. Tonga is not a wealthy country and the Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources does not have funds or personnel to patrol or protect marine reserves in Tongatapu, let alone the other three major island groups. If marine sanctuaries are to work in Tonga, the people must make them work.

The Strategy for the Community Based Phase

Finally, In June of 1987, after a year of watching the clams sit on a reef just offshore of their offices, the Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources allowed me to begin the public awareness project outlined below in the Vava'u Island Group. The outline gives all the information on what we did to accomplish this program.

I decided to proceed in partnership with Earthwatch International.

Earthwatch International, finds people who would like to assist with field research and puts them together with scientists who need assistance. The volunteers include people from all walks of life and include graduate students, professors, school teachers, doctors, lawyers, and all races, religions, and ages from 16 to 85.

Teams of 8 to 12 volunteers came to Tonga to spend two weeks doing surveys of the existing stocks of giant clams. They helped make videos, prepare educational material, and provided some excellent suggestions and insights into the central issue of getting the Tongan people to set up a sanctuary and look after it.

The Earthwatch volunteers played another important role. Each team member arrived in the small island community brimming with exactly the qualities we were trying to instill in the islander's culture;

- a love and concern for the environment and all living creatures

- a willingness to pitch in and help just for the pleasure of it

- a desire to learn new concepts about the sea

The natural friendliness and curiosity of the people of Vava'u inevitably discovered these qualities - but not before a hundred rumors and theories circulated about what all these people were REALLY after. When they found out volunteers were paying to spend their time trying to solve the problem of the Giant Clam's survival, the Tongans could simply not comprehend why. But eventually, after more than 200 volunteers came to Vava'u over a 5 year period, some of the message got through.

I had done quite a bit of reading about other projects that tried to change community behavior patterns. One of the most instructive community based management and monitoring projects was conducted by the University of Manila on Sumilon Island in the central Philippine islands (Russ & Alcala 1994).

The coral reef fisheries there, as in most of the Philippines, was in serious decline from overfishing and destructive fishing techniques. University scientists convinced the villagers to set aside a portion of the reef as a community coral reef reserve. Fishers monitored their catch and after several years it became clear that the reserve was helping. Fishers were catching more fish from less coastal area than before the reserve was set up. After ten years, the University researchers felt the project was a success and they disbanded the project. The villagers held a town meeting and voted to allow fishing in the reserve. It was soon destroyed and fishing catches fell to the low level experienced before the project started.

The moral to this story is that the presence and influence of the university researchers convinced the villagers to try the reserve. But the personal relationships within the community were held in check, with a multitude of issues unresolved, by the presence of the research program, and its personnel. When the researchers left, the relationships resumed exactly where they left off a decade earlier and the reserve boundaries were ignored by fishermen. In the long run the project failed - but the moral of the story is clear:

Communities have to work out their own social adjustments in advance and do the project because they actually understand the ecological reason behind the plan and agree, as a community, to go ahead with it.

So my game plan was to stay as far behind the scenes as possible and try to get the community, as a whole to install and protect the Giant Clam Santuary.

Our official and public position was that we were documenting the extinction of a species. If the people wanted to prevent the extinction of one of their favorite food species, our team would be happy to give suggestions. But the whole social and legal problem of how people could get the clams, set up a community sanctuary, and protect the clams was their affair, not mine.

I was not friendly. I refused to go to feasts. I did not accept any of the invitations of friendships with local individuals or families. I didn't go to people's homes. I didn't pay any local people to do anything. I studied clams with the express purpose of watching the people of Vava'u extinguish a valuable species.

When Tongan people suggested they would try to set up a giant clam sanctuary, I gave advice on biological questions and scientific matters quickly and publicly. I shrugged when they talked about social and legal issues. Most of the time I was off surveying the reefs - highly visible with my team of volunteers taking measurements, waving flags, shouting back and forth near the villages.

We began base-line surveys determine the condition of the existing stock of giant clams and to study the environmental conditions suitable for future giant clam sanctuaries. We also prepared educational materials had had private and public meetings to discuss the giant clam problem. We conducted surveys to find out what the people of Vava'u knew about giant clams, and to quiz them about what they might think of giant clam sanctuaries.

Key people make all the difference

In any community there are really nice, helpful people. These people will quickly understand the whole issue and help out in any way they can - because of the issue, not for any other reason. Such people are not common, and they are invaluable to successful community change. The Governor of Vava'u, Dr. S. Ma'afu Tupou, (later acting Minister of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources and now deceased), was one of these special people. He knew all about our project, and understood what I was trying to do, why I was doing it, and what the true issues were. He helped out in every way he could.

To overcome the disbelief in the perilous state of the species, the Governor arranged, in December, 1987 for the local business community to set up a small fund for cash prizes for the fishermen who could catch the most Tridacna derasa (Tokanoa molemole) and Tridacna squamosa (Matahele) to put into a community sanctuary. Our preliminary surveys were about to be believed. During the public awareness surrounding the contest we put shells of the already extinct Hippopus hippopus on display at Fisheries. The older fishermen remembered them, said they tasted very good and lived in shallow water. The contest offered $100 cash for any live specimens found. Nobody found any, and the idea of extinction took on a tangible meaning.

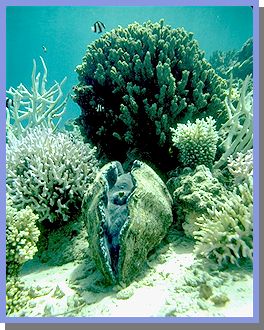

Fishermen searched for two months and only found 12 Tridacna derasa, underscoring the severe depletion of the local stocks in the inner island group of Vava'u. Finally, during a calm spell, the fishermen were able to reach more remote reefs and gather more, enough to build a respectable brood stock. Two community brood stocks were made, one with the 72 Tridacna derasa and another with 75 Tridacna squamosa. They were placed in shallow water (3-15 Meters) directly in front of Falevai village, on Kapa Island in a centrally located part of the Vava'u Island Group.

The Governor chose the village. It was in a central location, offered a good habitat for the clams, and most importantly, the District Officer lived there and was one of those special key people who truly understood and cared about the problem. The fact that the District Police Station was right there was also an asset.

The clams were arranged in circles so they could be easily counted and so the eggs and sperm would be well mixed during spawning no matter which direction the water currents were flowing at the time. Each circle had ten clams: nine around the circumference spaced at least two meters apart and one in the center. The circles, each about 10 meters in diameter, were laid out in depths from 4 to 15 meters in a site selected by the village people. Each circle had only one species in it and the Tridacna derasa circles were grouped in one part of the sanctuary and the Tridacna squamosa circles in another.

The district officer, Vanisi Fakatulolo, took charge of overseeing the protection of the giant clam brood stock. On behalf of the community, he obtained a permit under an old fisheries "fish fence" law to protect the stock in the clam reserve (this law was repealed in 1989 and the sanctuary has had no legal status since then).

Radio, newspaper and magazine articles informed the public of the need for, and the benefits of, the brood stock sanctuary. Fonos were held to tell the people in the 31 villages of the Vava'u Island Group to leave the giant clams alone.

In theory, nothing prevented people from using the sanctuary area for fishing or recreation. In practice, however, nobody did because if some clams were discovered missing, whoever had been seen swimming in the area would be blamed.

Mr. Fakatulolo notes, "Before this community project, some individuals tried to make their own private clam circles but in a small community someone will always have a score to settle and eventually the clams will be stolen and eaten. It is important to have the people know the new clam circles belong to everyone. Anyone can eat the young ones made by the circles but nobody can eat the ones in the sanctuary. If everyone understands, there is no problem with enforcement."

SOCIAL OBLIGATIONS

In Tonga, social obligations (Faka'apa'apa) are the most important aspect of a person's life. Allowing Tridacna derasa (Tokanoa molemole) to become extinct would be an unforgivable failure on the part of this generation of Tongans to fulfill the social obligations to future generations of Tongans. The major reason people have left the giant clams in the Falevai Community Giant Clam Sanctuary alone is because it is a social obligation to do so; a responsibility to maintain a good supply of these sea creatures for the families of all the people of Tonga.

"If a man allows his farm to go to ruin or spoils the soil, he is not meeting his social obligations to his family." explained Mr. Fakatulolo. "If anyone takes clams from the community sanctuary, he is spoiling the production of the sea and is not meeting his social obligations to himself, his family or his community."

"It's like planting a fruit tree," another Vava'u man said, "You have to wait for several years before it begins to produce fruit but then it goes on making plenty of fruit for everyone for many years." Since giant clams may live almost a century, the people of Vava'u could enjoy the fruits of the giant clam circles for generations to come. If the stocks are maintained by replacement of any which die, giant clams will always be a part of the Tongan diet.

In 1988, we made an educational video explaining, in English and in Tongan, the concept of the community giant clam sanctuary. In the video His Majesty King Taufa'ahau Tupou IV endorsed the project, saying, "The giant clam sanctuaries are a benefit to everyone and should not be raided by irresponsible people."

Operating according to my "it's your problem and your sanctuary plan" we spent almost no time surveying at the sanctuary itself. Whenever we wanted to go see the clams I went to the District officer and asked his permission. At one point I suggested perhaps they might operate a little tourism business, setting up an underwater trail through the giant clam sanctuaries, perhaps with a village guide. I was quite surprised at the reaction. Nobody went into the sanctuary. It was not for tourism. It was for the giant clams. The villagers did not even want tourists to know where it was and discouraged people from cruising yachts from entering the area. The only sign - on shore - said simply, "No Anchoring North of the Wharf. By order of the Police."

Also according to plan, we did not stay in Tonga. We came every year, spent two to three months surveying the wild stocks looking for recruitment, then left the sanctuary in the capable hands of the villagers. I'll admit when we came back after an absence of 9 months to find the clams still safe, it was a great pleasure and relief.

DO THE SANCTUARIES INCREASE RECRUITMENT ON ADJACENT CORAL REEFS?

There is little doubt sanctuaries work as they should for some plants and animals. Bird sanctuaries, for example, protect important nesting sites. If people leave the nesting birds alone, the population of birds will increase. But what about marine animals, like giant clams, with young that go through a free-swimming larval stage? The swimming stage might drift off with the ocean currents and settle on reefs far away - or perhaps sink at sea and die.

Prior to this study, there was little evidence to show marine sanctuaries would actually work to increase wild populations on nearby reefs.

Extensive base-line surveys began in June of 1987 and continued until the installation of the first community giant clam sanctuary at Falevai in January and February of 1988. Teams of divers surveyed the same stations again from July to October of 1988, 1989, and 1990. In all, survey teams covered more than 47 kilometers of shallow water reefs and spent more than 250 hours in the water actively mapping and searching for giant clams.

Scientific tests were set up to determine the impact of the broodstock of giant clams in the sanctuary on nearby recruitment.

There was no evidence of recruitment of the smooth giant clam Tridacna derasa prior to the installation of the sanctuary. Surveys from 1987 to 1988 showed overfishing had seriously endangered this species in the inner island group of Vava'u and lowered the adult stock below levels required for successful recruitment. Only 18 adults were located in the entire inner island area of Vava'u.

The first juvenile Tridacna derasa appeared eight months after the sanctuary was installed. The numbers of juveniles increased in 1989 and again in 1990, on reefs adjacent to the sanctuary and extending up to 8 kilometers away. By the end of 1989, survey teams had found more juvenile Tridacna derasa in the inner island group of Vava'u than have been recorded from the all the surveys on giant clams on the Great Barrier Reef combined. In 1990 the number of juvenile Tridacna derasa almost doubled. The total found in 1989 and 1990 probably exceeds the number of wild juvenile Tridacna derasa from all the surveys made in the Pacific combined.

A brood stock of the rough giant clam, Tridacna squamosa, was also included in the sanctuary. Settlement rates of these increased in parallel with, and geographically linked to Tridacna derasa settlement.

The data support the concept of community-based marine sanctuaries as a method of conservation of giant clams in rural island areas.

The people of Falevai

Village knew the project was successful even before the survey team scientifically

confirmed it. "The people found many baby vasuva on the reefs near the village and on

Nuku and A'a Islands," said Vanisi Fakatulolo. "The children brought them home

and ate them. Now everyone knows why they should leave the big ones alone in the

sanctuary. They can see the results. We have never seen so many baby clams on these reefs

before."

The people of Falevai

Village knew the project was successful even before the survey team scientifically

confirmed it. "The people found many baby vasuva on the reefs near the village and on

Nuku and A'a Islands," said Vanisi Fakatulolo. "The children brought them home

and ate them. Now everyone knows why they should leave the big ones alone in the

sanctuary. They can see the results. We have never seen so many baby clams on these reefs

before."

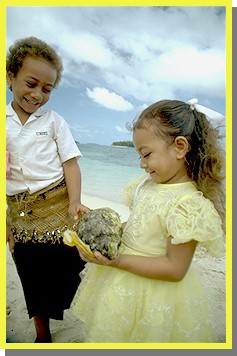

Vanisi Fakatulolo's daughter was born the same year the sanctuary was set up. I took this photo in 1993. The clam came from the first settlement of juveniles from the sanctuary and is the same age as the girl.

THE REAL SUCCESS

The real test of the project was not how many juvenile clams could be found on the reefs, but if the community changed its behavior and attitude towards their marine resources.

The people of Falevai and neighboring villages passed the test. They left the giant clams in the sanctuary essentially unharmed for six years. Interviews showed the village people protected the clams because they understood the reason for the sanctuaries and had a strong sense of community loyalty.

Surveys taken when the project was first begun showed the people did not, at that time, believe it was possible to leave giant clams in shallow water off a village without constant guard. Today, this attitude has changed and a new community confidence has emerged for working together to improve the marine resources.

What happens, in such a system, if the public trust is violated? In 1989 five clams were stolen from the sanctuary. The loss was quickly discovered and the culprit found. In a small island community little passes unnoticed. I asked Vanisi Fakatulolo how the community dealt with the problem.

He said, "A group of men got together and went to see the man who took the clams. We told him to come with us and took him down to the reef at low tide. I showed him some baby Tokanoa molemole and some baby Matahele on the reef. We told him these are the result of the giant clam circles in the sanctuary and they were for everyone's benefit. We told him each big clam in the sanctuary will make thousands of baby clams. When he steals a big clam from the sanctuary, he is stealing thousands of baby clams from everyone in the village. Now he understands and will never touch them again.'

There is no greater determent to poaching from a sanctuary than the displeasure of one's friends and neighbors.

The Ministry of Fisheries encouraged the presentation of an award for `The Best Clam Sanctuary' during the annual agriculture show. The award was presented by His Royal Majesty, King Taufa'ahau Tupou IV. As soon as the award was announced, in July of 1990, ten other Vava'u villages asked the Fisheries Department to help them set up their own giant clam sanctuaries.

The United Nations South Pacific Aquaculture Development Programme (FAO/UNDP) supplied funds to pay local fishermen to find more large giant clams for the new sanctuaries. By September, fishermen were able to collect enough clams from the remote reef areas to build three more sanctuaries, each with 50 Tridacna derasa and 50 Tridacna squamosa. To be perfectly honest, there was no biological reason to have 100 clams in the sanctuary. I insisted on that as a minimum number for success because it would be a serious personal temptation for thieves to have so many clams so close to the village. This made it something important and valuable to protect. In addition, it removed that many more clams from the wild stocks which had no protection whatever.

EFFECTIVE EDUCATIONAL MATERIALS (VIDEO)

Island governments need educational materials aimed at rural island audiences explaining - in island terms and local languages - what marine sanctuaries and reserves mean to the future of the community and how the people can help (Hudson 1984a).

In the Vava'u project, video was the most effective means of communicating these complex ideas. Although the literacy rate is high in Tonga, rural island people do not often read and they don't absorb complex ideas via radio programs. Fonos and churches are ritualized and involve very little opportunity for the introduction of novel, complex ideas. Schools are staffed with underpaid and often transient teachers struggling to deal with the whole range of educational issues. Island people are reluctant to talk with each other about new issues they don't fully understand. But everybody likes to watch videos, and today, video players are common in almost all schools and many homes. Even in the remote island villages in Vava'u the people have access to at least one machine.

Vava'u people saw the 30-minute video, "The Giant Clam Circles of Vava'u," again and again. There was an English and a Tongan version. Copies were given to the schools and to two of the villages where clam sanctuaries were established. It was broadcast on local TV many times. Copies were in all the video rental shops - often loaned for free. `Aisea Tuipulotu, Officer in Charge of the Fisheries Department in Vava'u, said, "The video was very helpful for us. It is very difficult to get people to understand something new and takes a lot of talking. Even then, they don't always believe you. But the video shows them, in pictures, what it is all about and they understand."

A second, more dramatic video on the sanctuaries was made in 1990 and widely distributed throughout the community. The Tongan name was "Do not kill the mother of all Tokanoa." The Tongan cast was entirely local fishermen and villagers. There was a Tongan language version and a Special English version. Surveys in 1993 indicate that more than half of the Vava'u community saw and understood the video. It was still being actively viewed in 1993.

TEN YEARS LATER

We continued to return to Vava'u for two to three months of survey work every year for six years. The clams were still there last time I looked. I understand new circles have been set up in the Ha'apai Group and in Tongatapu and they are doing OK. The Tongan example was also followed in Fiji and Vanuatu.

The concept of gathering scattered adult giant clams and placing them in protected areas to enhance spawning success and improve local recruitment has been strongly recommended by many fishery scientists including, Adams et al (1988), Lewis et al (1988), Sims and Howard (1988), Alcala (1988), Beckvar (1981), Gwyther and Munro (1981), and Munro (1986). The major problem was theft of the clams from the protected areas.

Theft problems have been reported almost everywhere giant clam hatchery work or brood stock attempts have been attempted. Government organized brood stock or hatchery production clams have been stolen in Western Samoa (Gawel, personal communication), The Cook Islands (Sims and Howard 1988), American Samoa (Buckley and Itano 1988), Yap (Price and Fagolimul 1988), and the Philippines (Estacion 1988).

Marine parks and sanctuaries have been unsuccessful in many Pacific nations because they are extremely difficult to patrol. The people who have traditionally fished these areas are not normally consulted before the establishment of the park. If the government attempts to prevent traditional use of the resource without common consent, it can only lead to trouble.

In Tonga, permanently restricted areas of the sea's resources, where no fishing may go on, is against ancient cultural practices (IDEC 1990 and Halapua 1982). Chesher (1984) and Paine (1989) reported habitual violation of the marine reserves in Tongatapu. Johannes (1982) reported similar problems in Western Samoa. When an underwater trail and clam reserve was set up in the Pangaimotu Reef Reserve in Nuku'alofa in 1989, the Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources attempted to enforce a ban on fishing in the area. Six months later the underwater trail was destroyed and the brood stock of giant clams killed. This may have been a protest by people who habitually fished the area and did not understand why they should be excluded.

The Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources abandoned surveillance of the original clam sanctuary in Nuku'alofa harbor in 1989. By 1993 only 22 clams were left. Many (most?) of the clams were borrowed by the Fisheries people for their giant clam hatchery project.

In Vava'u, the early attempts to create giant clam sanctuaries by individuals were failures. One individual set up a private giant clam sanctuary in the hope it would bring him aid money - not because he understood the concepts involved or cared about providing future generations of Tongans with giant clams. If he could get a boat, diving equipment, or cash, he was all for the idea. Governments can sometimes act the same way and the availability of large sums of money to assist island governments to set up parks and reserves does not, by itself, do much to foster a genuine understanding of the issues. While the reserves exist on paper, their boundaries may not be respected by the public and therefore, do not exist as a biological fact. Where individuals or government agencies attempt to set up giant clam reserves there has been and will continue to be problems with theft.

The success of the Vava'u community giant clam sanctuary project was based on a sincere effort to include public participation and to call upon the community spirit to change its destructive behavior to a new, constructive morality towards its natural resources.

Reaching out to the public was a difficult and time-consuming process. It also went against the general attitude of some government workers who saw themselves as different from the public. This problem resolved itself when the Fisheries Giant Clam hatchery project shifted into Japanese Aid hands. The Japanese advisors appreciated the concept of sea ranching, as they call it, and saw the benefits of forging a partnership with the village people. They helped set up several other giant clam sanctuaries where the villagers looked after the brood stock and the fishery personnel delivered seedling clams from their hatchery. The villagers help cultivate the young clams during their grow-out phase and either sell the clams, eat them, or add them to their brood stocks.

CULTURAL PRECEDENTS

In Pacific island nations where village reef rights were once practiced, restricted areas meant outsiders could not fish without permission, but the reef areas were not closed to residents. Some parts of a reef were restricted, from time to time, allowing it to recover. But such areas were normally re-opened for fishing after a short time (Johannes 1977, 1978, 1982, 1984a,b).

Community reserves for giant clams existed in other areas in the past. MacLean (1978) reported the people of Manus Island in Papua New Guinea collected giant clams and placed them in protected areas on the reef. These clams were left alone until long periods of bad weather prohibited normal fishing activities. Then they were used as emergency food supplies. I observed stocks of relocated and protected giant clams in the Shortlands Islands of the Solomon Islands and near Tagula in Papua New Guinea (Chesher 1980). The Tagula stock was subsequently destroyed by Fisheries personnel in an attempt to export the meat (which rotted and was thrown out).

Senator A.U. Fuimaono of American Samoa remembers, during the 1940's the villagers on Manono and Apolima Islands in Western Samoa kept stocks of giant clams off their villages on the shallow reef, collecting them while small and allowing them to grow in "gardens". Reports of protected giant clams placed near villages have also come from Savaii in Western Samoa.

Govan et al (1988) report some local individuals in Marovo Lagoon in the Solomon Islands are now maintaining clam gardens for conservation purposes. Alcala (1988) reports fishing communities and individuals at four island sites in the Philippines are maintaining protected areas for broodstocks of giant clams and ocean nursery sites for juveniles raised in hatcheries.

Community marine sanctuaries and reserves do work in Pacific islands, providing they are based on common understanding and are supported and protected by the local people. This is a question of education (Hudson 1984a) and spiritual commitment.

COMMUNITY SANCTUARIES COULD HELP MANY ISLAND AREAS

The loss of the giant clams throughout the Pacific is tied to a widespread lack of appreciation or understanding of the coral reef environment combined with a rapid increase in the availability of tools to destroy the coral reef habitats. This is why the Tongan giant clam sanctuaries are so important. They are easy to understand, cost very little, and are aimed directly at the major issues: the biology of the clams and the psychology of the people.

The giant clam sanctuaries of Tonga represent a new approach to conservation of marine resources in island environments. Other kinds of sea creatures might respond well to small community-based brood stock sanctuaries, thus allowing the people of the islands to rebuild and perhaps exceed the natural productivity of the sea.

Vanuatu Village Based Giant Clam Sanctuaries

In 1991, having heard of the Tongan Giant Clam Sanctuaries, two villages in Vanuatu set up their own Giant Clam sanctuaries using the booklet I prepared for the Tongan Giant Clam Sanctuary programme (funded by the United Nations FAO South Pacific Aquaculture Programme). In 1998 the Vanuatu sanctuaries were still going strong and the one in the southern Meskalyne Islands had over 1,000 giant clams and many of these were thought to be second generation juveniles from the original sanctuary. Most important of all, the villagers set up the sanctuaries by themselves, for themselves, with only helpful advice from the Fisheries Department.

[[NOTE: The Vanuatu Giant Clam sanctaries are still in existence in 2011]]

OUTLINE FOR A SUCCESSFUL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM

DEFINITION: A successful environmental improvement program changes the way people behave so there is a measurable improvement in the flora, fauna, or condition of a resource.

THE TEST: Success must be determined by a measurable change in behavior of the public and in the resource. Establish how to measure this first.

THE PROBLEM

The Giant Clam Tridacna derasa is almost extinct in Tonga.

- Big clams are the ones which make eggs.

- People are eating all the big clams.

- The Tongan public is not aware of this.

THE TESTS

- People will be aware of the problem and willing to help.

- People will leave the giant clams in the sanctuary alone.

- More giant clams will be found on the reefs.

THE STRATEGY

Get people to understand:

- There is a shortage of big clams

- Soon there may be no more big clams

- Only the people can help the clams

Assure legal protection (never done)

Get the people to restore ability of clams to survive

- Collect scattered adult Tridacna derasa

- Tag them and place them together in shallow water

- Leave them alone to produce young

- Maintain the population of adults

- Eat only smaller clams outside the reserves

ACTION PLAN

Communicate the problem and strategy to the people

- Written media

- Radio

- Meetings

- Fonos

- Fisheries/Fishermen

- Personal talks with Town Officers

- Churches

- Coconut Grapevine

- One on One volunteer surveys

- Video

Organize Activities

- Fishermen's Contest to Collect clams

- Advertising for contest outlines problem

- Cash awards from community establishes community ownership of clams.

- Use Community Clams for brood stock

- Governor selects village

- Geographic Position of Village assures larvae stay in area

- Security

- Willingness of Village people to help

- Village selects local site for clams

- Within easy sight of village center

- Not so close or shallow drunks or kids can get them.

- Where boats do not anchor

- With clean water, no fresh water run-off or rivers.

- Sheltered from waves

- Good tidal flushing

- Upcurrent or centrally located in island group so larvae do not wash out to sea.

- 2 to 15 Meters deep

- Oceanic salinity, temperatures 26-31oC.

- Coarse, thin sand or rubble with scattered live corals.

- District and/or Town Officer must

- Talk to village people

- Select location for sanctuary

- Obtain village sanctuary license

- Keep an eye on brood stock

- Give periodic talks to people

Give the clams a chance

- Install the circles of adults

- Leave them alone

CHECKING TO SEE IF IT WORKS

- Do the people understand?

- Pubic surveys

- Evaluate and supply more information

- Are the Community Clams OK?

- Map each clam, its size and condition

- Remap clams every few months

- If any are missing, report this to community

- Is the Brood Stock making young?

- Establish survey stations around inner islands

- Map all clams at each station

- Remap stations at yearly intervals

- Determine recruitment of brood stock species and measure change produced by sanctuary.

- Report results to community

REVISE ACTION PLAN AS NEEDED

- To keep the giant clams in the brood stock unmolested

- To increase recruitment and survival of young

- To encourage more community brood stocks

- To make giant clam brood stocks a cultural tradition.

FOLLOW-THROUGH

- Establish yearly prizes for best giant clam sanctuary

- Survey circles on regular basis

- Include educational materials in schools

- Make video about success to replay each environmental awareness week.

REFERENCES

Chesher, R.H. 1989. "Giant Clam Circles in the Vava'u Island Group of the Kingdom of Tonga. 1987 to 1989." Report to the Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources, Government of Tonga. 47pp.

Chesher, R.H. 1991a. "Tonga's Community Giant Clam Sanctuaries: A successful environmental improvement project." Report to the Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources of the Kingdom of Tonga. 22pp.

Chesher, R.H. 1991b. "Community giant clam sanctuaries: do they increase recruitment on adjacent coral reefs?" Report to the Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources of the Kingdom of Tonga.45pp.

Chesher, R.H. 1991c. "Giant clams of Vava'u, Tonga: their growth, mortality, habitats, predators and diseases." Report to the Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources of the Kingdom of Tonga.47pp.

Popular Press Publications

Chesher, R.H. 1987. "Tokanoa contest winners get cash prizes - pass the word, don't touch the clams in the clam circles, they belong to everyone." Voice, Nuku'alofa, Tonga. 3 pages.

Chesher, R.H. 1987. "Vasuva dying out? Are you the cause?" Tonga Chronicle Dec.11, 1987, p.5.

Chesher, R.H. 1987. "Teu fe'auhi uku Tokanoa 'i Vava'u." Tonga Chronicle Dec. 11, 1987, p. 5.

Chesher, R.H. 1989. "Giant clams again breeding in Vava'u waters." The Tonga Chronicle. Vol.26(9):1.

Chesher, R.H. 1989. "Return of the Giant Clams." Earthwatch June.

Chesher, R.H. 1989. "Giant clam circles save species from extinction." Matangi Tonga 4(5):18-

Chesher, R.H. 1990. "Tonga's Precious Coral Reefs Abused and Broken." Matangi Tonga 5(1):32/33

Chesher, R.H. 1990. "Pausi'i mo maumau'i 'a e feo 'o Tonga." Matangi Tonga 5(3):34-35.

Chesher, R.H. 1991. "Turning the Tide for Clams." Pacific Islands Monthly. March:25.

Chesher, R.H. 1991. "Ko E Ngaahi Tefito'i Me'a Mahu'inga `E 12 Ke Toe Lahi Angeai `A E Vasuva." with Ulungamanu Fa'anunu. South Pacific Aquaculture Development Project. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. Suva, Fiji. 12pp.