10 Hot Tips for Facilitators

For successful environmental improvement projects in the Pacific islands

10 key ingredients for successful integration of environmental information into economic decision making:

- Involve all interested parties

- Promote changes in action, not words

- Change people's perspectives

- A vision with measurable milestones and regular reviews succeeds.

- Facilitators must avoid manipulating people's motives.

- Information programs work when they address the information needs of the community.

- Community information programs need active links to National research.

- Enjoyable projects are popular projects.

- Quality control of the research is essential

- Information gets used when presented in an

entertaining, understandable, and available media.

1) Involve all interested parties

Key strengths of Pacific islanders (see SWOT analysis) include their ability to work together on community projects, their ability to solve conflict by negotiation and unanimity, and their willingness to co-operate on international matters. When planning or policy making starts off with everyone being informed and allowed to participate in the formation of the planning agenda and setting of research goals, sustainable activities are more likely to become reality. Examples of good co-operation were the regional organizations planning process, tourism development, community fisheries plans and the Vanuatu Land Use Planning Project.

2) Promote changes in action, not words

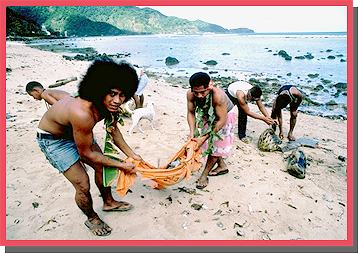

A group of young men clean up a litter-strewn beach in American Samoa as part of an Island Beautification programme. |

People need to be involved in action, not just words. The whole thrust of public awareness and education efforts is based on providing information about environmental issues, but raising awareness is not enough.

An environmental improvement plan must change the behavior of the people so there is a measurable improvement in the flora, fauna or other resource.

Changing what people know or think does not necessarily change what they do on a day to day basis. Any plan - economic, physical, or social - will be defeated if it does not focus on actual physical behavior of the interested parties. This is easy to say, but changing people's day to day habits is the hardest task imaginable. It is the failure point of all of the billions of dollars spent on sustainable development plans in the past thirty five years of global environmental concern. People develop habits and their moment to moment behavior is cross-linked a thousand ways, each act reinforcing the other.

3) Action helps change people's perspectives

The SWOT analysis pointed to a need to improve a sense of self-sufficiency in contrast to the pervasive "dependency role" assumed by many communities (and Governments). This is a major problem for all improvement programs, the very act of assisting can promote further dependency.

A planner or government agent cannot change anybody's habits. People have to change their own habits. When they do change their habits, people do it instantly. It does not take time to change a habit pattern, but it may take decades or even a lifetime to get around to doing it. It is hard for even one person to change their habits - even when they know it in their own best interests. It turns out to be (surprisingly) easier for a group to change their behavior pattern together because the individuals assist each other in the process. The participatory approach, as seen in the example of farm research in Fiji, helps farmers and government workers actively work together to examine and solve agricultural problems.

4) A vision with measurable milestones and regular reviews succeeds.

There is no way to judge or review the success of a plan without having a measurable indicator to see if the plan is working. An plan that is not reviewed shortly becomes a plan that does not exist. Expert planners in the corporate field insist that a plan that is not reviewed every three months is forgotten by the people involved. The PNG coastal fisheries development programme is an example of the use of targets and indicators. There are a host of examples of projects that fail because of a lack of follow-up, review and revision. It is a common failing even in participatory exercises.

5) Facilitators must avoid manipulating people's motives.

Motivation was a recurring problem for involvement in environment and sustainability exercises. In any planning, or research for planning, the future success of the project rests on the motivation of the people. Getting started for the wrong reason results in an unsustainable programme.

Experienced facilitators know that they must exercise the greatest care not to influence people's motivation. People have to decide for themselves why they should or should not adopt sustainable practices. A facilitator might be forced to debase certain expectations (no, there is no money to be earned by participating) but to question or manipulate motives is to endanger the sincerity of voluntary participation and the sustainability of the programme.

Design of community participation programs must, however, avoid falling into the obvious pitfalls that lead to people's involvement for the wrong reasons. Here is a list of common motivations behind becoming involved in the process of sustainable policy and planning.

The dependency of Pacific island regional organizations and national government agencies on foreign funding has often been the key motivation for accepting involvement in projects of any sort. The creation of Environmental Units within national government agencies were done with the understanding that this would create additional funding opportunities in the international funding arena. Even local projects begin with the theme that, in the end, people will benefit financially. When people become involved because they think (or know) they will be paid or will somehow get money or equipment from their participation, the plan will only succeed as long as the money or equipment continues to materialize. When funds dry up the project fails.

Cash enterprises in rural areas, and accounting of all kinds, are weaknesses of Pacific island rural communities. Cash motivations for projects always seem to cause strife as people focus on the money and not the issue. I don't know why environmentalists feel they have to bribe people to cooperate in environmental programs. The environmentalists themselves are almost always motivated by spiritual or ethical feelings and work their tails off with precious little financial support.

A development plan will hopefully result in increasing earnings of the people of the community, but this is quite different from the process of planning, environmental assessment and monitoring. Money is also a miserable motive for environmental improvement programs because environmental improvement policy decisions are, by their nature, altruistic.

NGOs and novice practitioners of participatory techniques believe the social cohesiveness of Pacific islanders and their willingness to share and sense of friendliness and humor can help induce villagers to do a project based on personal friendship. This approach is difficult to avoid since people in the rural parts of the Pacific are friendly and hospitable. More than that, there is almost a scramble to latch onto and incorporate an outsider into the extended family.

In Polynesia, an expatriate who works with communities will be invited to be a part of the family. This is not a polite euphemism, they mean it seriously. Of course, in an extended family what belongs to one belongs to all so having an outsider (enormously rich in comparison to local standards) brings good fortune and social status to the favored family.

There are two pitfalls to this. First, the advisor becomes the cause of change. When that person leaves, the project terminates. Second, there are intricate and extensive arrays of social relationships in small villages. Joining one family (either literally or in action) will split the community's motivation to participate in the plan along the invisible lines of social forces.

This is a common motivating force, closely paralleling the motivation for independence from colonialism. In the Vanuatu participatory forest reserve project, a transcribed account of one villager's version of the meeting made it clear that his interest was establishing ownership boundaries and control. There is good reason for his concern. Land control is the most contentious problem in rural Pacific island settings. People are forever bickering about who owns what land or who controls what land.

In Melanesia, custom land is particularly prone to disputes. Custom land is generally an unsurveyed section of the island defined by rivers (that may change course), rocks, trees, or shorelines. Ownership of custom land is collective but may be divided into a group whose ancestors arrived first and a group of late arrivals who get to use the land, but only at the discretion of the first group. Land boundaries within the custom land are even less distinct than the custom land itself. The potential for strife abounds.

Forming a partnership with the government means that whichever group does it gains greater control and a clear (even surveyed) definition of who owns what land. The price, in the Vanuatu forest project, was tacitly set by the Government as allowing a part of the land to become a community forest reserve. A small price, considering that if the people later decided to violate the agreement it would not mean the loss of the land.

Individual Church leaders have been important in the environmental movement in the Pacific islands (the Foundation for the Peoples of the South Pacific, the Solomon Island Development Trust, and other NGOs were started and managed by clergy), but the Church itself has not been active in many environmental programs in the Pacific islands.

Willingness to agree to and act upon environmental plans is ALWAYS against the immediate best interests of the individual (otherwise people would act sustainably of their own accord). The only real motivation to restrain one's greedy impulses is a moral and spiritual understanding that the individual is not the Centre of the universe, but part of a larger and more important system of life. This understanding is the very heart of the extended family and one-talk system and the source of energy for the remarkable success of the Church in the Pacific islands. Deliberately doing something to harm the family, the one-talk system or the Church is not allowed.

In the Pacific islands, respect for God's plan is already integrated with respect for the extended family and one-talk system; acting against one is acting against the other. Working in accordance with His plan is likely to be more completely understood than working in accordance with a Department of the Environment plan for environmental sustainability. The Church has begun to mobilize its forces to assist in the battle to protect God's creation.

The majority of people enjoy doing good and helpful acts because they are nice. They don't need any other reason. The key is to find nice people in the society and work with them. There are inevitably going to be people who are not nice, but these usually go along with the programme so long as it is beneficial to the majority or at least not threatening to them, personally. Everyone in the community knows who is nice and who is nasty and people in rural villages have long since decided how to deal with the mean ones. A major problem for outside agents, including government workers, is having the project captured by the local con-artist (there always is one). If this happens, materials meant for the whole village will be sequestered away or the con-artist will use the project as a method of personal leverage against others in the village.

Projects work best when the material benefits expected address basic issues, such as more food, better health, and interesting things to do - things nice people are interested in promoting.

6) Information programs work when they address the information needs of the community.

The successes of participatory programs are greatest when they focus on environmental assessment and monitoring that addresses information needs of communities as well as those of scientific or technical experts. Participatory Assessment and Monitoring involves the community in all aspects of the study of their own situation - measuring, recording, collecting, processing and communicating information (Atherton et al 1996, Chambers 1994a,b,c).

Information gathering is more efficient and effective when directly linked with a community vision. The measurements should show if the community's goals are actually being reached. A practical and attainable vision works, even if the goals don't seem very earth shaking. It should not cover ten thousand things at once or start out with the most difficult problems (like land tenure or family planning). On the other hand the vision should not be trivial either.

People caught up in the process of researching something of interest to their own lives quickly learn the critical issues and become real advocates for environmental sustainability. Research is a process of learning. Everyone involved has the opportunity to share what they know and learn from each other and from the resource being investigated. The volunteer research team will soon be very interested in the information, and become more so as they gather information themselves.

7) Community information programs need links to National research

The success of volunteer research depends on its applicability to the community, but part of the feeling of value comes from participating in real science that is of use to the nation and even the world. When data from school projects is valuable to the national or international effort to solve environmental projects, the programme is much more vital.

- Research information from the community level can be a key element in national policy decisions and macroeconomic planning.

- Information on the vision of the community is essential in harmonizing government policy and planning with what will actually be possible in practice.

- Information on the community and district goals and time-frames harmonize conflicts between sector, national, and international expectations.

- Information on subsistence agriculture and fishing is the kind of data that can be used by communities and by the national agriculture, fisheries and economic development officers.

- Information on stream water quality enables monitoring of the performance of timber and mining companies while also recording the progress of communities in not polluting their own water supplies.

- Information on forest use and tree growth can be incorporated into the National Forest Inventory GIS - provided the research officer sets up the survey and measurement methods so the community land-care group can easily and accurately gather and supply the information.

8) Enjoyable projects are popular projects.

Research is a process of discovery anyone enjoys. Outdoor, action oriented research is especially interesting compared to research that involves the talking or reading kind. People enjoy team sports and challenging outdoor activities. Surveying, monitoring, and investigating the living world and one's relationship to it is an absorbing way to spend an afternoon.

The Australian Waterwatch programme includes a "Bug Detective" kit that enables school children to determine water quality by identifying insect larvae and other small organisms caught using standard entrapment techniques. The Streamwatch "Murder under the Microscope" project is a national success with thousands of schools participating in the game of detecting what causes the death of indicator species in waterways. The game was played using experts to provide data and clues on radio broadcasts.

9) Quality control of the research is essential

Volunteer assessment and monitoring programs are frequently criticized by professional scientists as lacking quality control. Tests in the United States and Australia showed that community and school monitoring groups obtained replicate data of equal quality to that gathered by professionals from the same test sites (Ellett & Mayio 1990) providing professionals were involved in training the volunteers and that quality control was a part of the programme from the outset.

The research design must compensate for people who have no formal scientific training. By judicious selection of the indicators and methods of measurement, the results can be more than accurate enough to satisfy the intended purpose.

To the non-specialist, written reports are confusing, boring, and hard to obtain. Information presentation is as critical as the information collection process. Remember that island people don't spend a lot of time reading, but everyone appreciates graphics and pictures. One New Zealand community that studied shellfish populations in a community beach reserve recorded their findings on the increase of the populations each year as artistic graphs imprinted on ceramic tiles. These were cemented onto a wall that leads onto the beach.

Information compiled on water quality measurements taken by primary school children in Australia are published in a colorful Streamwatch newsletter called the "Wiggly Worm."

The Vanuatu Community Forest-Use Awareness project, the SPARCE project and the Tongan Giant Clam program found video an extremely helpful media to present otherwise complex ideas.