Participatory integration of planning and policy making

LogFrame Training Kit | Vanuatu Land Use Planning Project | Tourism Policy

Existing participatory research and management in the Pacific islands takes place within the centrally defined policy and planning process of the Government. This is entirely different from the process recommended by Agenda 21 that involves all participants in the policy making and planning process. Here are some examples of bridging the gap between the local, provincial, national and international planners.

The Pacific Regional Agriculture Programme LogFrame Training Kit.

Government attempts to use participatory techniques have been fruitful, but the vast majority of government agencies are untrained in these tools. Regional organizations are now starting to assist governments in training officials in forming working partnerships with the farmers, fishers and foresters. The Pacific Regional Agriculture Programme, for example, produced a Logical Framework Training Kit (1996) as a participatory communication tool for the Pacific.

Recognizing the inefficiency of the fragmented institutional structures in the agricultural sector, the PRAP selected the Logical Framework (LogFrame) method to plan, monitor and evaluate agricultural projects. LogFrame was devised by the US Agency for International Development to help evaluate technical co-operation projects. It quickly became a versatile tool for participatory communication and planning because of its ability to overcome institutional barriers.

Vanuatu, Samoa, Tonga, Fiji and PNG field tested the LogFrame Participatory Process and the case studies are the foundation for the Logical Framework Training Kit. The kit contains a manual, overhead transparencies in PowerPoint format and a PowerPoint slide-show on diskette.

Judging by the success of participatory research and community management trials, the Pacific island countries will be adopting this approach as a cost-effective methodology for resource assessment and monitoring. (Available from Pacific Regional Agricultural Programme, Project 11 Agricultural Rural Development. Private Mail Bag, Suva, Fiji. FAX: (670) 315 075.

Linking the participatory process with national level policy making - Vanuatu's Land Use Planning CARMA project.

To be effective, participation in local-level planning must be an extension of the national planning and policy process. But how should the participatory process link with sectoral and national level policy processes?

The Participatory and Integrated Policy Process (PIP) was designed as a way to promote the involvement of all stakeholders in the policy process and harmonize the conflicting objectives, strategies and capacities in economic and physical planning (Campbell & Townsley 1996). The system is based on the flow of information and the process of getting the information.

As with the above examples of participatory research, the key is to involve the interested parties in defining their economic, social and technical needs, their priorities, and their own proposed solutions. The process is as important as the information obtained, maybe more so. People know (or think they know) what they want and need. They appreciate being asked. They like it even more when they have the opportunity and responsibility to have a say in what the government intends doing with their land and their resources.

This is not limited to villagers. The professional and technical staff of government have information they wish to contribute about resource needs, priorities and solutions in their sector. They often realize there are links with other sectors that are not working and are on the front line of economic and environmental failures in Pacific island countries. One reason professional staff leave government employment is their inability to apply their knowledge to influence policy decisions.

The Vanuatu Land Use Planning Project

The Vanuatu Land Use Planning Project, initiated by AusAid in late 1995, is an effort to:

- Build up skills and resources to strengthen land use planning and natural resources management capabilities; and

- Develop effective mechanisms to ensure that land use plans prepared at National, Provincial and community levels are consistent and are implemented.

- Particular emphasis will be placed on strengthening Provincial planning capabilities since this is where much of the implementation will stem from.

The National Land Use Plan integrates a broad set of principles and guidelines for development of land resources, supported by information from Development Plan 4 (DP 4), the natural resources inventory (VANRIS), the National Conservation Strategy, the National Tourism Management Plan, and data collected by line agencies and other groups such as census data, data relating to agriculture, forestry, geology and mines, rural water supply and cultural heritage. These agencies and groups are involved in the development of the national land use plan, and their endorsement is critical to successful implementation.

The project established the Vanuatu Land Use Planning Office (VLUPO), to carry out the tasks at national level, and to train staff and co-ordinate planning activities in the Provinces. At Provincial level, the project assists in developing Provincial Development Plans and natural resources management capabilities within the office of the Provincial Planner.

At the community level, the project assists villagers in the process of developing land use plans utilizes a Community Area Resource Management Activity (CARMA) "Bridging the Gap." The project's overall strategy is to create land use plans that integrate between local, provincial and national levels and across all sectors.

The first step is to assemble a multi-sector team of extension agents as a Technical Advisory Group (TAG) in each province. The group is led by the Provincial Planner and includes extension officers from agriculture, forestry, livestock, fisheries, lands, rural business, health, education, water supply, public works, woman's affairs, youth council, and NGOs.

The National Land Use Planning team provides a 7 day training course that includes a variety of PRA type tools. During the course the participants develop ideas on the most important problems in the various villages in their province and gradually select specific village areas for the site of a CARMA activity. Once sites are selected, the team identifies the potential and suitability of land resources for development using information from VANRIS, local knowledge and other sources. This information is plotted onto a MapInfo GIS.

A land planning map compiled prior to a community meeting.

The colored maps are a useful focus tools for the TAG preliminary meeting with the villagers to identify major land use problems. Following the first meeting, the TAG team organizes a CARMA program with the villagers to map the area and identify the problems and aspirations facing the villagers. The CARMA program will use TAG extension agents from forestry, agriculture, fisheries, health or whatever agency might be appropriate for that particular village's problems.

Once the problems are identified, the agents work with the villagers in finding solutions at three levels: community, provincial, national. What do the villagers need to do? What must the Province do? What are the National Government responsibilities? One example of this process was the need for a health clinic in one village. The integrated team approach resulted in the community building the building, the provincial government providing the furnishing, and the national government providing the medical staff and medicine.

The final land use action plan is produced as a revised map, showing what everyone has agreed on for the use of specific parcels of land and detailing responsibilities for the projects. The participating agencies have a data sharing agreement so the information can be used by the whole team and standardized to put into the VANRIS with its FoxPro interface. The project has simplified the MapInfo menus so it is very easy for officials to make maps to support their part of the action program. Presently more than 30 agencies actively use and add to the VANRIS GIS.

The AusAid funded project is expected to directly assist in developing a CARMAP in one community in each Province. This will provide necessary training and experience for TAG members. Thereafter, the TAG will continue the process in other interested communities under the guidance of the VLUPO. The VLUPO will assist the TAG and interested communities in implement their plans through identifying sources of funding. As of November, 1997, 6 TAG training programs and 6 CARMA were completed in 4 Provinces. Four of the CARMA workshops were the first level - done with the supervision of the national staff. There have been 2 secondary workshops, done by local and provincial people trained in the TAG workshops. This demonstrates the training works and the trainees can conduct the CARMA locally.

The participating government agencies agree that the process is successful and will become more so as more people are trained in the process and the villagers themselves begin to understand how they can actively participate in the future. Observers note that Forestry Officers trained in group processes in the earlier workshop have used their training and talents to help other extension agents in the TAG training activities. The major concern of the participants is the question of how the process should be institutionalized when the current project terminates.

The Vanuatu project is a close approximation of an idealized PIP process. It is considerably different from the normal policy making process in the Pacific Islands. Although the Vanuatu example does not incorporate all phases of PIP in it's current stage, it is an excellent example of the how elements of the process can be started.

The PIP process has been called The Pacific Way where it exists on an inter-governmental level. The PIP pattern of co-operation, problem identification and policy formation is behind the formation of the numerous regional organizations and regional policies. If the various nations of the Pacific were parts of a larger Pacific Community called Oceania:

- The South Pacific Forum, made up of the heads of government of the South Pacific Countries would be the executive, forming policy decisions and acting through the Forum Secretariat.

- The South Pacific Organizations Coordinating Committee (SPOCC), made up of the heads of the regional organizations with the Forum Secretariat as Chair would be a Cabinet.

- The SPC Statistics Programme would be the Statistics Division of Oceania.

- FFA would be the Ministry of High Seas Fisheries,

- The SPC Inshore Fisheries Programme could be considered the Ministry of Coastal Fisheries of Oceania.

- The Pacific Forum Line is Oceania's Ministry of Transport.

- SPREP is Oceania's Ministry for the Environment.

- SOPAC is Oceania's water utility board, and mineral resources department.

- The SPC Agriculture Programme is the Oceania's Ministry of Agriculture.

- The Heads of Forestry Meeting is Oceania's Forestry Department.

- The Pacific Islands Labor Ministers Conference is Oceania's Ministry for Labor.

- The Pacific Islands Tourism Development Council and the Tourism Council of the South Pacific are the Ministry of Tourism.

- The University of the South Pacific might be considered Oceania's Ministry for Education.

These organizations function from the bottom up, not from the top down. The Forum Secretariat acts according to the directives and needs of the member countries. The Forum Fisheries Agency does not tell member nations what to do with the fishery resource and can make no demands on the countries. It acts as their representative in negotiations with foreign fishing nations, co-ordinates research, and facilitates common policy decisions to meet the needs of its member countries.

Each nation on the governing body of the regional organizations has an equal say in the policy and planning process, so the regional organizations represent their needs and visions. The interests of various member countries are harmonized between the participating governments in an equitable fashion - the round tables, review of the available information by experts, oratory by top level government officials, tiny Tuvalu having equal say as big Fiji, Samoa with a small tuna resource with a voice as powerful as Kiribati or PNG with enormous tuna resources.

Respect for all members and their views is of paramount importance to this process. Information is available to any member without restriction and data is collected and kept in libraries and databases ready to be used to solve agricultural or fisheries or forestry problems. Requests for information are handled by trained librarians and statisticians. Environmental, economic and political data presented at meetings of the FFA, the South Pacific Forum, and the South Pacific Conference are the foundations for a multitude of economic and physical planning decisions for each nation and for the region at the same time.

However, the process of harmonization works best for resources and activities that are themselves regional; like the tuna resource or a ban on long gill nets at sea. When it comes to actual changes in the behavior of people in the individual island countries, or resources like forestry or local environmental and development issues, the process is much less effective. Real, on the ground progress will improve dramatically as the participatory approach develops to bridge the gap between the regional/national and the district/village interests.

At ground level, regional organizations are suddenly too small, unable to obtain timely environmental information from the far flung islands or reach the motivating level of people who use (and abuse) the resources or of government officials that manage the resources. While the organizations can't reach out to interact with the resource users, representatives of the resource users can reach out to the organizations. This process will be facilitated by the growth of the Internet throughout the islands. When resource users are able to contribute to the policy formation and decision making process that goes on around the round tables of Oceania's various regional organizations, the entire system will finally reach ground level. The current attempt to incorporate the needs of the people of the region has prompted regional organizations, to try participatory methods in field investigations, workshops, and surveys. And they help.

As the SWOT analysis demonstrated Participatory Integrated Planning (PIP) can help offset the expected drop in foreign donations to Pacific island countries and regional organizations.

Island governments can't conduct expensive research programs or environmental projects (such as National Forest Inventories or Water Resources Surveys) without foreign funds and expertise. The regional organizations of Oceania also depend on foreign funds to conduct expensive research programs. Top-down research and development projects, and legislative and planning efforts of governments are expensive and inefficient. The high rate of development programme failure, masked by a pandemic refusal to review programs to determine their long term results, cannot be sustained as foreign allowances are reduced.

The Pacific island governments will, therefore, be forced to adopt cost-effective methods of information gathering, devolving the responsibility for planning and conducting research to communities themselves, with the National government offering technical advice and perhaps some key equipment to help develop research policy and methods and to co-ordinate information storage and retrieval. The government agencies would mirror the current strategies of regional organizations, providing advice and technical support to their "member" provinces and villages.

Just as the regional organizations expect countries to pay for their own field work costs today, governments must expect communities to pay for their own resource assessment planning and monitoring programs. Today, equipment, methods, and information networking is donated to the governments by foreign aid. Tomorrow, governments will be expected to aid communities by donating equipment, methodologies, and information.

Ideally, national governments will be able to accord the same relationship to community leaders that national leaders now enjoy within regional organizations. The concept of the government assuming the role of a regional organization for communities is not far from the political methodology described as "The Pacific Way," but it is a major diversion from the colonial government mentality that the communities are not ready or able to assume responsibility for their own behavior or participate in the decision making process. This is exactly the sentiments behind the colonial service in the Solomon Islands not including Solomon Islanders in the decision making process until 1972.

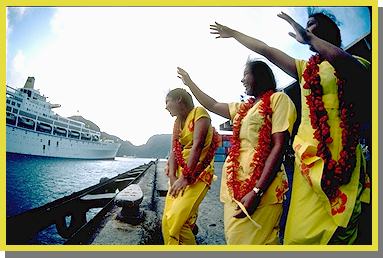

Tourism development and the Participatory Process

Perhaps the best example of integration and co-operation of regional, national and local resources - both governmental and private - for sustainable economic development and planning is the tourism industry.

The tourism sector has used participatory

research techniques for years. They also have a sound sustainable

development policy.

The tourism sector has used participatory

research techniques for years. They also have a sound sustainable

development policy.

The Pacific Islands Tourism Development Council, the Tourism Council of the South Pacific and national tourism organizations have used participatory methods in economic and physical planning for years. The tourism industry was the first to publish a comprehensive regional environmental strategy which includes EIAs as a mandatory step for any major tourist development.

On the national level, visitors are asked to fill out cards on arrival, and sometimes on departure, describing why they came to visit and sometimes what they liked about their visit and what they didn't like. These data are accumulated and analyzed by the national statistics offices and by the regional organizations. Policy and planning decisions of these on-going surveys then influence all aspects of development in the tourism industry. The survey process is extended to the people in the tourism industry and in the public sector of the community to find out their problems and successes with tourism. Most islands have tourist associations that act as NGO focal points for national and regional tourism officers. The information is current and incorporates environmental impacts and considerations.

This information is passed on to the local tourist industry associations to help them improve their performance. Regional assistance is available for training and advice. Government tourism officers are often organizers of local environmental events and speak on tourism and environmental issues at local schools.

Tourism integrates a broad sector of the island community, Agriculture, Fisheries, Conservation, Parks and Recreation, Water and Energy, Sanitation, Health, Roads, Construction, Mining, Transport, Lands and Survey, Education, Arts, Crafts, and Culture. In general, where tourism is sought in the Pacific islands, people seem to work together between these areas; co-operating well for what they perceive as a common benefit.

The lesson from the Tourism sector is one of mutual co-operation at all levels, and a general pervasive understanding that success depends on maintaining the beauty and cleanliness of the environment.